Housing projects set up by collectively organised citizens are not a new phenomenon. However, there is still a lot to learn for architects. Because they do not work for, but together with the future residents, their role is constantly changing. Sometimes they are fellow residents, sometimes they share the collective’s vision, sometimes they have an innovative vision of living themselves, and sometimes they co-design as part of a large team. These roles have in common that they require a new set of ‘soft’ skills.

By Darinka Czischke, with input from Sara Brysch and Stephanie Zeulevoet

*A Dutch version of this article was originally published in De Architect magazine on 29 June 2021. This English version has been edited by the author.

Across Europe, a variety of collective, self-organized, and participatory forms of housing have been around for over a century. Think, for example, of housing cooperatives, cohousing, intentional communities, eco-villages, Community Land Trusts (CLTs), and a wide range of similar models. I bring these large geographical variants of collective self-organised housing under the umbrella term ‘collaborative housing’.

In the Netherlands, collaborative housing emerged in the 1980s as ‘Centraal Wonen’, the Dutch version of the cohousing model that originated in Scandinavian countries in the late 1960s. More recently, the ‘wooncoöperatie’ (housing cooperative) is gaining ground, and the popularity of cluster homes for seniors, such as De Knarrenhof, is increasing. Elsewhere in Europe, collaborative housing models include Bofeaelleskab (Denmark), Kollektivhus (Sweden), Baugruppen (Germany, Austria), Genossenschaften (Switzerland, Austria, Germany), Habitat Participatif (France), Miethäusersyndikat (Germany and more recently variants thereof in Austria and the Netherlands), Community Land Trusts (England, Belgium, France) and cooperativas con cesión de uso (Spain). Although collective self-organization in housing has a long tradition, the aim of the recent wave of initiatives is to tackle current social problems. This should lead to wider social inclusion and cohesion, affordability, and stricter requirements for environmental sustainability.

Walter Segal, N. John Habraken, Christopher Alexander, and Frans van der Werf are architects who have already explored similar design models and strategies in the past. They wanted to make it possible for residents to appropriate and produce space. While there is a growing awareness in various sectors and disciplines that resident involvement is important, many architects and professionals in the built environment still have the idea of the architect as an ‘all-knowing’ expert. End users are seen as passive ‘clients’.

In addition, most architects cherish the desire to leave their personal mark through their designs. This view ignores the resources and creativity that end users can bring in as co-designers (co-creators) of their own housing and living environment. Due to the growing digitization of society, lay people have increasingly better access to online self-education and training. This changes the value of professionals, demanding from them new tools and ‘soft’ skills such as teamwork, process guidance and joint decision-making.

In addition, factors such as time, planning, regulations, and financial frameworks do not make developing collaborative housing initiatives any easier. Resident groups usually lack the experience and knowledge, which are necessary to negotiate the complex procedures involved in housing. They also encounter resistance from mainstream development partners: designers, engineers, planners, housing corporations and financiers. They often regard these types of projects as too complex and too risky. Nevertheless, the current collaborative housing wave creates new professional roles that assist groups in development and construction procedures. This also applies to architects.

The architect as co-resident

In many collaborative housing projects, architects are part of the resident group. They play a leading role in the construction and management aspects of the project. In these cases, the boundaries between the professional and the personal are blurred, as evidenced by the cooperative cohousing project La Borda (Barcelona, Spain), where two residents are also the architects of the project (architecture firm La Col). As a result, they were more closely involved in the project and more committed.

During some of the meetings, they had to remind the group that they were the architect. They participated in all meetings of the group’s ‘architectural committee’. This committee was made up of six or seven residents who met every two weeks for the first few months to compile the material to be discussed at the general meeting. The participation of the architects in all meetings ensured the necessary professional expertise and guidance when discussing design matters.

This was not the case with the collaborative housing projects they did afterwards. They were involved in this purely professionally and only participated in a few meetings. In addition, they spent more time on La Borda as it was the first project of its kind, and they lacked the experience and expertise. They eventually learned a lot through trial and error. For example, they regret the large degree of self-construction and that they have not engaged a single contractor.

The ‘benevolent’ architect

The outspoken vision of collective clients requires an architect who can translate the vision and who also feels involved. This is why groups often approach architectural firms that are known for their open attitude towards collaborating with their clients. Or they find a specific aspect of their knowledge important, such as environmental sustainability.

For example, the initiators of Le Village Vertical (Villeurbane, France) – people eligible for social housing – wanted to live in a housing project that met their ecological and social standards. They also wanted to open up the project to very low-income households, such as the unemployed and other socially disadvantaged people. Low-income households would benefit greatly from a lower energy bill by living in an energy-efficient building, but also from the solidarity of the group as a whole. The group chose Detry-Levy & Associés, an architectural firm with knowledge of ecological construction and that matched their wishes in this field. It was the first time that this architectural firm worked on a resident-led housing project. According to one of the initiators, the architects invested a lot of time in this process. Although it was not a huge commercial success, they found the experience they had gained valuable.

In the Swedish cohousing project ‘Sofielunds’ (Malmö, Sweden), the architectural firm Kanozi defined its role as mediator. This means that they guided the collective design process and democratic decision-making. The architects translated the residents’ wishes into one coherent design. Residents were involved in almost all design decisions, such as environmental sustainability (high energy-efficiency), lower construction costs (smaller units, fewer elevators/stairs, no parking, outdoor galleries that double as balconies) and more community-oriented construction (collective spaces kitchens with a view of the outside galleries, outside galleries as balconies). Although the process took longer than a standard project, the result was to the satisfaction of the resident group. The project also added value to the neighbourhood in terms of architectural quality and visual integration into the environment.

The ‘visionary’ architect

Projects are also started by architects with their own ‘vision’ on housing. This is often based on their own ideas about architecture and its role in society. A good example is the housing project for women [ro*sa]²², in the 22nd district of Vienna (Austria). The initiator was architect Sabine Pollak of the architectural firm Köb & Pollak, who is interested in gender and housing. She wanted to develop a collaborative housing project that would meet the needs of women. Pollak was of the opinion that not only the wishes, but also the knowledge of the future residents should be part of the project planning.

In 2002 she organised discussions about her project idea through various feminist groups. Many women living alone attended these first meetings and indicated their preferences. Design elements that came up often were small apartments, good accessibility, many communal areas, and large transition zones between communal and private spaces. This led to the creation of [ro*sa] which further developed the ideas behind the project.

The architect as ‘co-designer’

In a number of cases, established housing providers, such as housing associations, adopt the principle of collaborating with residents. They develop ‘hybrid’ models for collaboration. A good example is the Dutch Space-S in Eindhoven, designed and developed jointly by the architectural firm Inbo, the housing corporation Woonbedrijf, and the future residents. The project started with an open call to future tenants who wanted to contribute, under the motto “Create your own Space-S!”. They also sought contact with certain marginalized groups that were invited through civil society organisations.

Designing together with such a large group of non-professionals required new design methods. There were workshops with mood boards where future residents could indicate which images appealed to them. There were also plans of apartments built 1:1 with foam blocks. According to the architects, despite the great resident involvement from day one, they kept themselves in charge by setting the right boundaries and asking questions behind the design, such as: “How do you spend your day?” or “If you have friends over, where do you sit? Do you sit in the living room and watch TV, or do you sit in the kitchen and cook together?”. This resulted in a much greater variety of plans compared to top-down projects and made it much more interesting for the architects to work on.

Towards co-creation

At Co-Lab Research, a research group on collaborative housing at the TU Delft Faculty of Architecture, we collected and developed the above examples. In this process, we gained insight into the benefits and problems that architects encountered in these projects. Architects interviewed find that working with residents’ collectives is more satisfying and creative than working with traditional clients. Some note that there is no need to compromise on creative freedom. They do, however, recognize that a broader set of skills is needed, especially to act as an architect and process facilitator. This does create tension in the sense that there must be a balance between the control of the users on the one hand and the influence of the ‘experts’ on the other.

In addition, these projects are generally considered to be extremely time-consuming and slow to implement. At the same time, a number of architects note that if there is good planning and management, collaborative housing does not necessarily have to be more time-consuming than traditional projects. Because more time has been invested in communication and consultation, the final design can ultimately be realized more quickly.

When it comes to the end result, collaborative housing also provides a more diverse range of housing types and thus enriches the architectural output. Building methods based on “DIT” (Do-It-Together) are also phased and constantly evolving, because they have to match the (changing) needs of residents and are aimed at long-term quality.

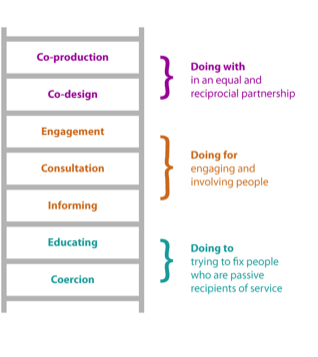

All in all, architects collaborating with residents’ collectives should opt for an approach aimed at co-creation or co-production. This means “(…) providing services in an equal and reciprocal relationship between professionals, people who use their services, their families and their neighbours” (New Economics Foundation, see Figure 1). This requires a fundamental change in the relationship between architects and end users. In this approach, residents are seen as active participants, not as passive clients. Architects who work with residents’ collectives must therefore have a special ‘vocation’ and a great affinity with the ideals of the group. They take on the role of process supervisor and are prepared to hand over ‘power’ to the residents by taking co-creation as a starting point.

Conclusion: Educating future architects for co-creation

There is still a long way to go to achieve innovative and effective working methods for architects who deal with collective clients. On the one hand, this is because architecture schools are slow to respond to this in their curriculum, particularly for students interested to learn about alternative ways to approach architecture, such as through co-creation. On the other hand, architecture students need new role models, as well as new tools. The emphasis should be less on ‘starchitects’ who travel the world to build the tallest skyscraper and stadiums. Architects who often work ‘under the radar’ with local, tailor-made, and user-centric approaches deserve a bigger podium. Because more diversity within the profession leads to more diverse planning and construction cultures, which in turn leads to more inclusive and liveable cities.

Acknowledgements: the authors would like to thank Merel Pit, editor-in-chief of De Architect magazine, for her insightful comments and editorial support with the original version of this article.